What the Puck is Happening in the Hockey Gear Market?

The two most dominant companies in the hockey gear market are both up for sale at the same time. Why?

My “illustrious” hockey career ended around 2016, when I transitioned full-time to rowing (a classic high school sports transition, of course). Fast forward to 2024, and I interrupted my retirement with my first visit to a hockey shop in nearly a decade. It felt like coming back to your childhood hometown after a long time away, with so many familiar sights and sounds but new faces I didn’t recognize. The store sold new gear brands I had never heard of, and talking to the store’s employees about the rise and fall of brands I used growing up piqued my interest enough to look up the current state of the hockey market only to find that the two largest companies, CCM and Bauer, are both up for sale right now. I felt like Troy walking into a chaotic apartment with pizzas in Community, and immediately asked “why?’

![Gif Remake] Community Pizza Gif : r/HighQualityGifs Gif Remake] Community Pizza Gif : r/HighQualityGifs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!W6E8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffa6110fc-0c5a-454e-a58b-f2d8f2916bb0_675x380.gif)

It’s worth knowing up front that CCM and Bauer currently dominate the hockey gear market, but have each changed ownership multiple times in the last 25 years. As a result, the current (new) ownership not realizing their desired growth may be the the clearest answer to my question above. If they were happy with company performance and trajectory, they likely wouldn’t be selling. Hockey is a relatively large international sport, but one with some interesting facets that directly affect its gear market. It’s extremely expensive relative to other sports, is generally limited to colder climates, has complicated rules, and is difficult to follow as a viewer without much past knowledge of the sport. Especially compared to skyrocketing sports like pro football, the general consensus that the overall hockey market hasn’t grown dramatically, but competition in the gear market has risen within it.

But how to actually demonstrate some of these qualitative mechanisms at work to pin down the reason two of the industry’s behemoths are leaving the market? First, it seems prudent to analyze trends in the size of the market itself, and second, to take a look at the balance of competition within it. As with any market assessment, it’s also important to highlight any recent and potential structural changes that might dramatically alter outlook for the future, in addition to accounting for some elements of chance in both overall market and constituent company growth.

Let’s lace ‘em up, shall we?

Hockey is an extremely interesting sport, especially when it comes to the professional game. It’s one of a handful of sports that have a relatively large global presence through multiple high-caliber professional leagues around the world, similar to basketball, baseball, or soccer. However, hockey is played almost exclusively in cold countries and regions in the northern hemisphere like the US, Russia, Canada, and Scandinavia. Even within the US, ice hockey really gravitates towards the northeast and upper midwest.

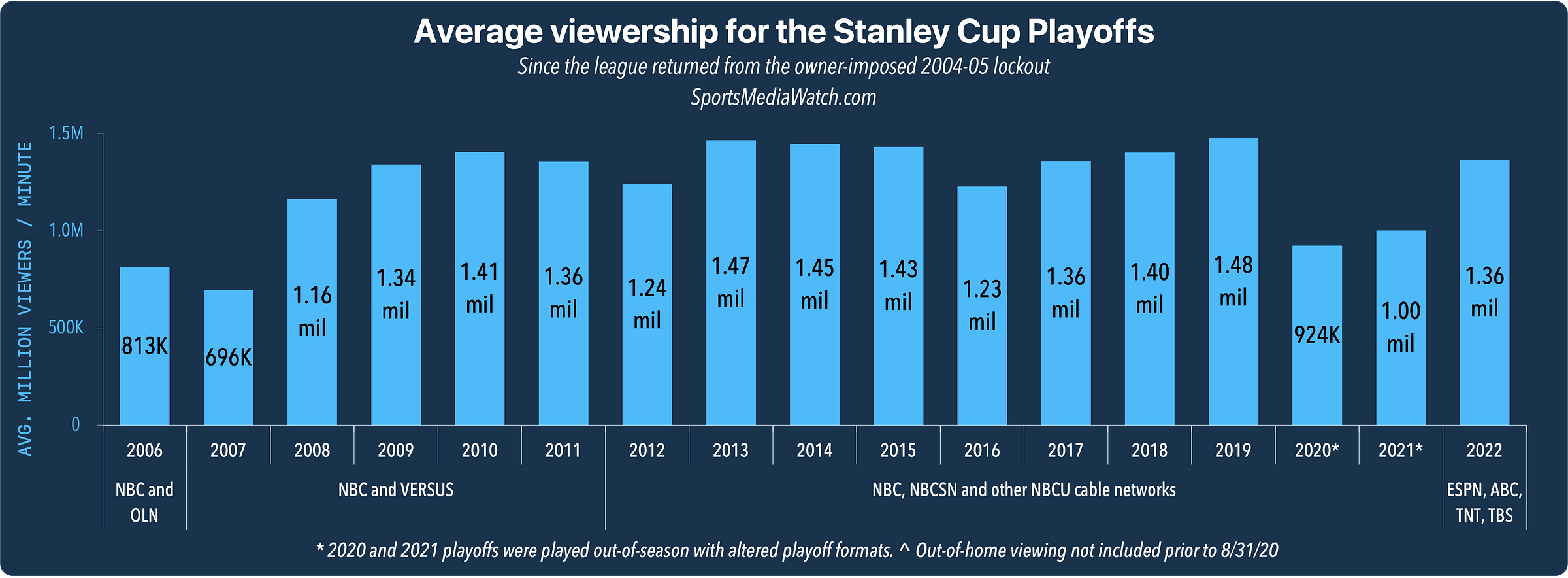

Hockey’s biggest league worldwide is the NHL in North America, which, despite its status as one of the “Big Four” sports in the US, hasn’t really grown much in popularity over the last couple decades. Relatively stagnant viewership of playoff games since 2006 highlights this trend, especially when compared to the average viewership growth throughout this period in other leagues like the NBA and NFL. It’s worth nothing, though, that in 2024 the NHL garnered record league-wide revenues, saw a 2000’s record viewership of 1.54 million viewers per playoff game, and launched a new team in Utah.

Despite the recent uptick in professional hockey popularity, if you looked at the graph above and thought “if TV viewership correlates to overall market interest in a sport, projections for hockey gear markets must not be optimistic,” I would be right there with you! But, it turns out, we’d both be wrong. In 2023, the general consensus is that the overall hockey equipment market totaled ~$2B in value, and nearly every public market research provider I could find (Grand View, Mordor Intelligence, Data Bridge, etc.) projects a relatively steady compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of the market between 4-6%.

I personally find this projection difficult to reconcile with the high-level viewership trends seen above on the professional stage, and even the growth of the game more broadly. US Hockey keeps pretty detailed count of its total registered players, and between 2010-2019 (pre-pandemic disruption), the number of registered hockey players in the US grew from 500,000 to ~570,000— a CAGR of only 1.4% during this period. A projected CAGR of 6.2% implies the total market value of hockey gear will double in just under 12 years, which I don’t quite see, absent another large inflationary period. While the US market does not account for all hockey players, it does compose ~1/3 of the global player base, with Canada following similar trends and accounting for another 1/3. It’s very possible my skepticism is misguided, but I would imagine that when you include the impacts of the pandemic, average hockey gear company growth has not met expectations.

However, I don’t think relatively conservative growth of the hockey gear market alone would instigate the type of company behavior common to the market in recent years. Since 2000, many companies have launched and retracted hockey product lines, including two large equipment companies Easton and Reebok. In addition, companies like Adidas, New Balance, and Nike have acquired hockey brands— CCM, Warrior, and Bauer respectively— only to turn around and offload the assets in about a decade (the one exception being that New Balance still owns Warrior). The biggest names in sports making acquisitions and subsequent sales in the hockey gear market has perpetuated the pattern of launching and killing hockey gear brands, helping spark many articles about the history of many now-shuttered companies or bringing back popular brands.

One of the big challenges in the hockey gear market that I think contributes to this type of behavior is the supremacy by the two biggest players— CCM and Bauer (Remember them? They are the ones that are up for sale right now!). Mordor Intelligence calls the hockey gear market “Consolidated,” and when you look at the breakdown of what brands NHL players use in-game, it’s clear this reputation is well-warranted. Bauer and CCM account for nearly 90% of professional hockey gear use in every market segment, ranging from skates to sticks to helmets. This balance has held relatively steady over the last decade, with some market entrants coming and going, but few making major dents in the market share cornered by these two giants.

This level of consolidation really amplifies the issue of stagnant overall growth in the hockey gear market. While smaller, newer hockey brands like True are still able to grow radically when compared to companies that already hold over 90% of the gear market, they face structural disadvantages in marketing, supply chain, and manufacturing that makes it difficult for them to really consume chunks of the market quickly. On the other hand, already-massive hockey gear companies have minimal growth upside because it is extremely difficult for them to grow or even sustain their share of the market— one that is not growing overall relative to other sports. The value of a company that already commands 50%+ market share in a market with minimal growth is a difficult investing prospect.

Beyond the high-level market dynamics, the actual sport of hockey and its constituent products place some limitation on the upside of gear companies. Companies in the market all seem to sell pretty disparate type of products in order to retain overall consumer mindshare, keep players in their ecosystem of products, and to make sure they are capturing a larger chunk of a small overall market. They typically offer a large set of helmets, advanced apparel, carbon fiber sticks, complex padding, and other products that are manufactured and assembly in completely different ways. Very often, the products are not highly differentiated from one another, and the fact hockey requires so much gear makes it prohibitively expensive for many.

A lot of companies like Easton, STX, and Warrior have leveraged similar product suites in sports like lacrosse and baseball. However, these relatively small companies are trying to offer a large variety of complex products (especially helmets and padding), and have generally decided to optimize around a sport, rather than a specific manufacturing expertise. It really would not surprise me if hockey gear companies tried to break out of the confines of the limited growth in the sport to manufacture other carbon fiber products like bikes or ski poles, but those are crowded market in their own right!

If I am a large hockey gear company like CCM and Bauer, my next step after looking at the market breakdown above would be to examine what might instigate an inflection point in hockey gear market growth. This is where we start to get into crystal ball type projections about a product market! I’ll offer some examples and relative likelihood of potential catalysts for rapid growth of hockey, but if I could predict these things accurately, I’d already be living my best life somewhere near the Kepler Track in New Zealand.

Individual super-stardom is a huge mover for the popularity of a sport or league, with Caitlin Clark and Leo Messi exploding the popularity of the WNBA and MLS respectively as great recent examples. The NHL has its fair share of international superstars like Connor McDavid, Alex Ovechkin and Sydney Crosby. Any playoff games with McDavid especially are, in my opinion, must-see TV. What’s interesting about these super stars is that they are on the level of the megastars of other sports in their home countries of Canada and Russia, but hockey rarely produces personalities that break into mainstream media in the US, or globally. I do think hockey players tend to be more reserved in public presence, interviews, and outreach than athletes in most other leagues, and I think a hockey gear manufacturer is probably not banking an individual star to come skyrocket the popularity of the whole sport to a new level.

On the flip side, I do think that hockey is uniquely positioned to generate growth by investing in its simpler adjacent markets and new media endeavors. It may not be strictly likely, but very possible that with some effort, the less gear-centric “dek” (street) hockey could explode in popularity in warmer parts of the US like Pickleball has. A rise in other adjacent markets like floorball, field hockey, or lacrosse could all spark growth in ice hockey as well— and make the on-ramp to hockey as a participant or viewer much more accessible. To supplement this slower “onboarding” process, the NHL’s television collaborations with ESPN and virtual cartoon broadcasts with Disney could make viewing more accessible among younger audiences especially (Disney’s broadcasts are very fun). In these regards, I would personally be pretty optimistic about potential acceleration of the growth of the sport accelerating.

Finally, as opposed to easing consumers past the current barriers to entry in the sport, it’s also interesting to think about potential mechanisms that could drop the overall cost of entry into ice hockey, expanding the player base as a result. New infrastructure products like advanced rink chillers or automated Zambonis could make it cheaper to launch and operate arenas in new areas. Or perhaps new business models for gear-as-a-service or re-using gear (similar to what I wrote about the outdoor gear market below) may alleviate some of the financial burden of the sport that is particularly painful as kids grow. Each of these examples punctuates my believe that there likely isn’t a single silver bullet that will accelerate the growth of the overall hockey industry, but a lot of individual outcomes could chip away at barriers to entry that eventually unlock exponential growth of the game.

How Long Until We Hit the GAAS (Gear as a Service) Pedal?

The outdoor gear market can be nothing if not overwhelming— mentally, emotionally, physically. Two weeks ago I began hunting for a new pair of trail running shoes and was overrun with so many options and reviews that I just hunted for any pair mentioned in a “Best Trail Running Shoes of 2024” article that was on sale at the time. As I was traveling to S…

Ice hockey and its flagship league in the NHL have existed for over 100 years at this point, so it’s not shocking to me that the sport and its gear market experience relatively large ebbs and flows in popularity and growth. While some of my thoughts above on future kickstarters to the overall industry paint a brighter potential future, the sport and especially its consolidated gear market have some structural disadvantages hampering that rapid growth.

After this research about the market and the recent history of its two biggest companies in CCM and Bauer, it doesn’t surprise me that the major public corporations and the PE funds who have owned these brands would be disappointed with their growth. While I don’t think the gear market instability caused by the constant acquisition-to-sale and launch-to-dissolve cycles of many gear brands has affected the growth of the overall sport, I really do think that hockey gear brand ownership entering the market with eyes wide open about the current trajectory, deficiencies, and opportunities really could help drive the sport itself forward.

I would love for hockey to explode in popularity and to reflect this article next time I step into a hockey shop ten years from now. Maybe by then, some of the notable bike manufacturers will have broken into the carbon fiber hockey stick game, or I’ll be able to pick from a selection of 10 brands, most of which produce products in other sports too! Crazier things have certainly happened, and if these new entrants push out my old-time incumbents in Bauer, and CCM, I’ll be able to say goodbye to them like the characters in the second best hockey movie of all time: Happy Gilmore.

The greatest hockey movie of all time is Miracle.