The Gold Standard of the Future?

The costs and structural challenges of hosting the modern Olympic games

It’s almost that time once again, where all across the United States we gather in front of our screens at random times in the day to watch a few countries dominate the Olympics. This year’s summer games in Paris carry a bit of extra personal meaning as it could have taken place in my backyard in Boston. A decade ago, Boston was selected as the US city to submit a bid to host these games, beating out Los Angeles (2028 host), San Francisco, and others. A couple months after being selected, Boston rescinded its bid, though the artifacts of our application are still available online, notably our pitch video:

Honestly, Boston put forward a pretty compelling pitch to host the Olympics, and think the city is actually somewhat well-positioned to host the summer games. We’ve got lots of professional and collegiate sporting venues nearby, different bodies of water for aquatic sports, enough dorms to host 5 Olympic contingents simultaneously, and infrastructure that we could likely upgrade enough in a decade to ensure the city didn’t collapse under the tourism surge. So why am I not preparing to rent out my Cambridge apartment next month for an exorbitant (but reasonable, of course) fee— why did Boston retract its summer Olympics bid?

Well, likely in a shock to no one, the answer is probably money!

The IOC breaks out the costs associated with the Olympics into three categories: Infrastructure, Sports Infrastructure, and Operating Costs. “Infrastructure” costs are those associated with general municipal upgrades not centered on sporting itself, so improvements to public transit, parks, air quality, and more. Often, cities and countries use these upgrades as a means to pitch constituent on hosting— in the case of Boston, unsuccessfully. “Sport Infrastructure” includes any assets created explicitly for sport— stadiums, tracks, ranges, ice rinks, ski runs— that host nations hope will have a life beyond the Olympics, but which often do not. Finally, “Operating Costs” encompass the staffing, housing rentals, TV coverage, etc. that are actually required to execute the games in real time.

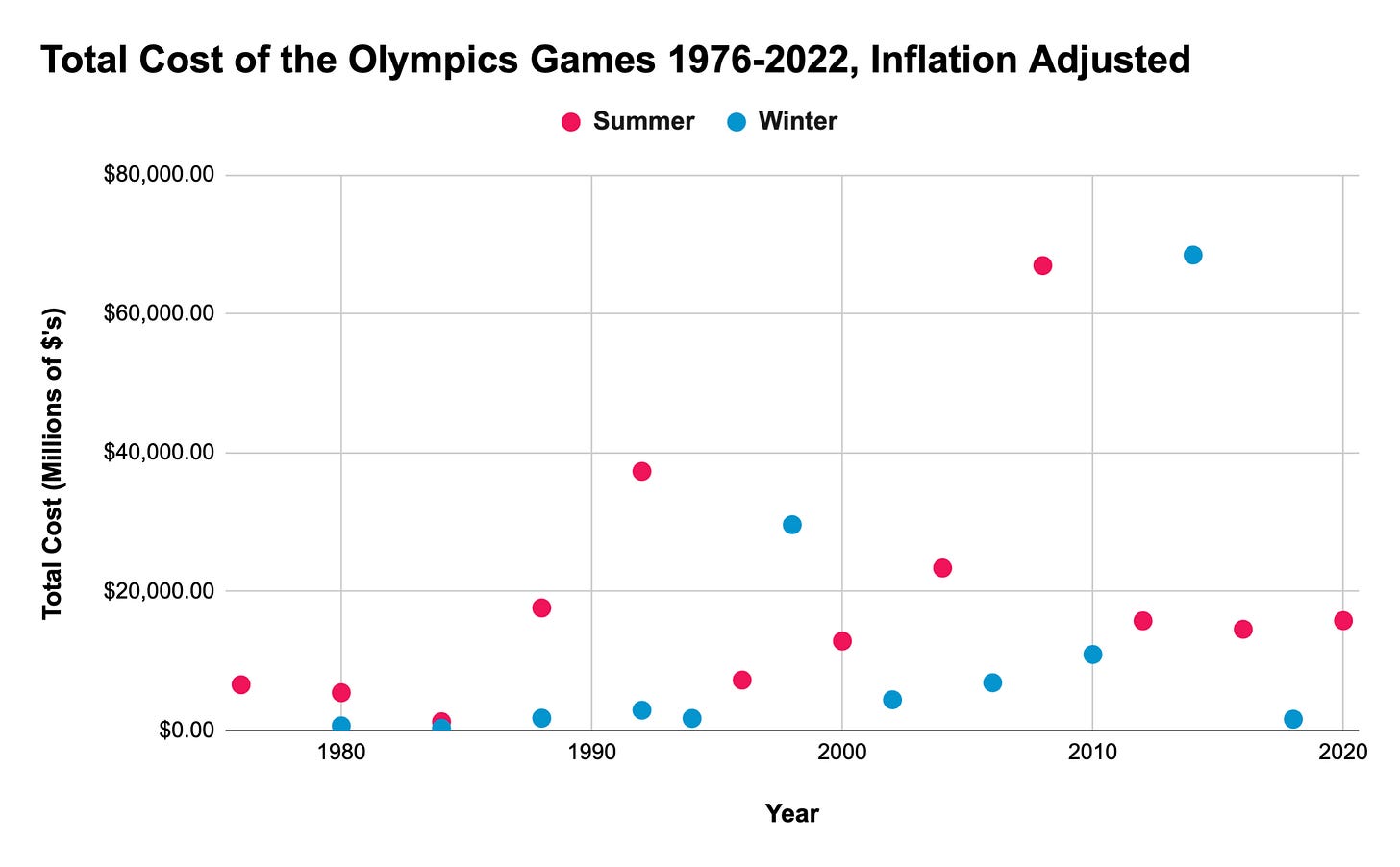

Breaking out costs into these individual categories implies a level of precision that could help answer the question: is hosting the Olympics a good investment? Spoilers, though, no one really knows the answer! Part of the reason is that the cost to host the Olympics has changed dramatically over time, and its difficult to anticipate how much it will cost a unique city to host. Detangling each of these cost categories and seeing through both intentional and unintentional obscuring of total Olympic-related costs makes it extremely difficult to overcome uncertainty related to the net impact of the Olympics. Additionally, there appear to be relatively large differences between the costs associated with the summer and winter games. These trends are visible in the following plot, showing an inflation-adjusted cost of hosting the Olympics in the last 50 years:

I’ve left trend lines off the plot above due to the high variability of hosting costs, especially in recent years, but it’s still easy to spot the lower average cost of the winter olympics (except Sochi in 2014). I believe there are a few major reasons for this split. First, more athletes compete in the summer games, which naturally draws larger crowds and requires more infrastructure. In the most recent Olympic cycle, nearly 5x the number of athletes competed in the Toyko summer games than the Beijing winter games, and often the divide is even greater historically.1 Second, the winter Olympics require more specialized infrastructure, the most basic being snow and mountains, which typically limits eligible bidders to those who already have most of the necessary expensive assets in place. Finally, a lot of winter Olympic hosts are located in more rural areas relative to the summer games, so there is typically less apatite for major “Infrastructure” costs— fewer bidders are pitching major subway or housing upgrades in smaller ski towns.

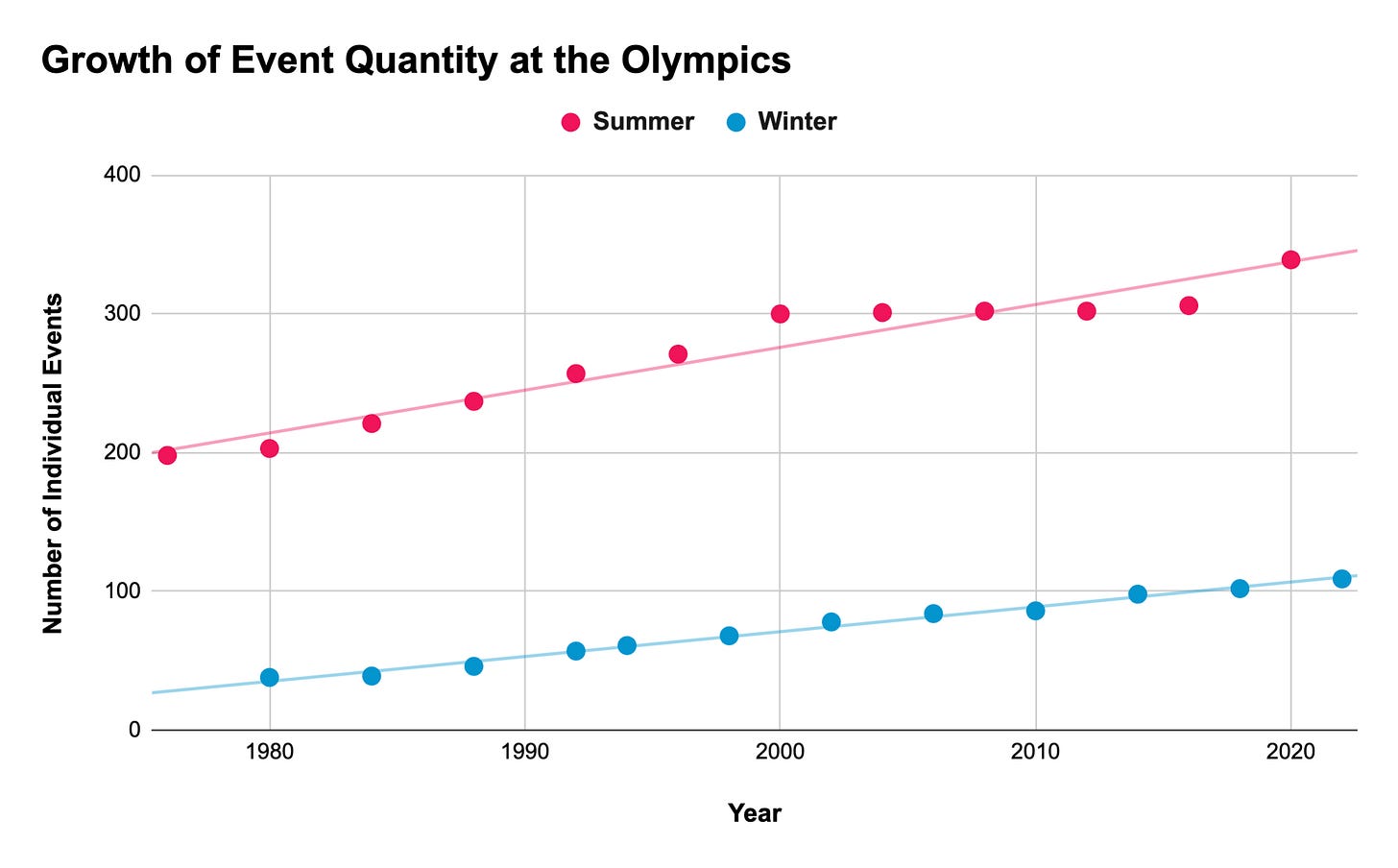

On top of this reduced winter Olympics hosting cost, we also can squint to see a general increase in the cost of hosting over time— though again, the data is very noisy and there are few samples. Although Olympic participation has roughly doubled since 1976, it’s stayed relatively level since 2000, with both the summer and winter games adding fewer than 1,000 athletes per Olympic cycle. However, the pageantry associated with the opening ceremonies and the fanfare of the games themselves has definitely increased over time— I’ll likely never forget actually seeing ‘The Nest” onscreen in Beijing for the first time, built just for the Olympics. Maybe most importantly, though, the number of individual sports and events has risen steadily since 1976, the beginning of our cost analysis. While I’m not able to exactly speculate if more expensive sports and events have been added to the summer and winter games, certainly there are more— and we keep adding additional ones!

I’m representing the connections between these insights and hosting costs as pure fact, but it’s worth noting the limitations of extracting precise insights from Olympic cost data. Despite the feeling that the Olympics have existed forever, the modern games only started in 1896, and only 54 Olympic games have been held in total— a small sample size that contracts even further when you consider that “accurate” cost-tracking didn’t start until ~1976, about 50 years ago. “Accurate” is in quotes here because there are a fair amount of conflicting sources for the cost of older Olympics, and it’s likely that many countries are not entirely forthcoming or simply able to produce accurate information related to Olympic-related costs and revenues. My favorite concrete example of this occurred when the vice secretary-general of the Nagano Olympic Bid Committee, Sumikazu Yamaguchi, had their expense records burned after the games had been completed.2

So what’s going on in Paris? The City of Light has no need for press coverage or tourism hype, and already has a fair amount of existing infrastructure by way of stadiums, public transit, bike lanes, and more. Despite this, the city seems to be investing heavily in making the games as big as possible, and has already invested over $1B to clean up the Seine for swimming (with mixed results), will host the opening ceremony on the river, and has constructed new venues around the city for events that could be hosted in existing stadiums. While I don’t expect the final bill to total more than the $60B of the 2008 and 2014 games, it’s clear that leadership of France and Paris are seeking non-financial returns on their investment. They may be aiming to help unify the country or generate positive press— seemingly common, but risky tactics that often backfire if the locals in the host city are negatively impacted by hosting the games.

If Paris is any indication of continuing increases in complexity and cost to host the Olympics, there are interesting implications for the future of the event as a whole. First, it simply makes hosting the games in individual, less affluent countries or cities difficult or even prohibitive. This in turn raises questions about whether or not the Olympics could be split across multiple host nations like the World Cup will be in 2026, or if it should be split up into more events (e.g. Winter, Fall, Summer, Spring games). We’ve already seen the IOC break esports out into its own Olympic cycle, so it will be interesting to see if they do the same for a subset of “traditional” sports in the future. If I had to guess, I would imagine that the next logical break point for this pursuit would be action sports like surfing, breaking, and skateboarding, which represent most of the recent additions to the summer games.

Part of the allure of the Olympics is its concentrated, central nature though. Take my breakout of sport categories too far, and you end up with the existing world championship system that already exists in most sports, just on a four-year cycle. In order to stay relevant with newer audiences, I really don’t believe IOC will stop adding new sports and events to either the summer or winter Olympics, either. Unrivaled size and spectacle are the hallmarks of the Olympics in the world of sports, so the IOC likely sees the easiest path in adapting to the future is to simply increase the scope and complexity of the games— though the key question will be: when does the elastic snap? When does hosting the Olympics become so expensive and difficult to execute that securing government funding from an individual country becomes impossible or a poorly-executed Olympics comes to fruition?

Currently, the IOC has reportedly made all host selections through the 2034 winter games in Salt Lake City. I would imagine that before 2050, so effectively within the next 25 years, the current Olympic structure will be broken down in some form, whether it is a significant retraction in the quantity of sporting events, a breakout of the games into multiple host cities/countries, or the distribution of sports into new Olympic games entirely. I see no reason the Olympics can continue to grow indefinitely, and no reason they won’t face enough competition in the modern attention economy that the IOC is forced to reshape the games dramatically.

Once the Olympics either change or prove that they are a sound financial investment, maybe Boston will finally step back into the ring and duke it out against other cities around the US for the ‘Racing Sports’ Olympics in 2052. If that happens, I’ll still be patiently waiting to rent out my apartment to the highest bidder on whatever home rental service is popular in the future.