Time is Money is More Enjoyment?

Investigating how investment in a new sport pays back in fun and fulfillment over time

The first weekend in April earlier this month, I made my first trip to the state of Texas for a reason even I would have doubted even last year: three days of non-stop golf (and more importantly a mini reunion with friends from undegrad). In three days, we played more holes of golf than I probably have in the rest of my life combined— a total of four 18-hole rounds on some very difficult courses + a long-drive competition + a par-3 course challenge. I lived up to my estimated 32-shot handicap, but had enough good putts and a chip-in for our team competition to feel satisfied. I had a blast the entire time and enjoyed just being out on the course taking my best crack at the ball. Naturally, I capped off the trip watching Rory McIlroy finally win his first Masters while pounding a Jamba Juice açaí bowl at the sprawling DFW airport.

You couldn’t really ask for a better weekend on any front, or at least I couldn’t.

I landed home in Boston at 1am on Monday morning absolutely exhausted, with zero regrets. I was nursing a bad early-April sunburn (I could never live in Texas due to the heat) and one question stuck in the back of my mind: What now?

It’s a question that I’m sure countless people have asked themselves when they first ignite a spark of interest in a new hobby. For me, the question of how to handle this newfound excitement about golf has so many variables that it’s difficult to even assess the spark itself. It could be that I loved the weekend of golf because of its novelty to me as a player, or because I thoroughly enjoy the social experience on the course, or because the technology aspects of the sport are extremely interesting (I did see one of the fun little robot car caddies carrying another players’ clubs around the course and was jealous). Perhaps I could have done nearly any activity over the course of three days with my friends from college and I would have enjoyed it enough to be interested in it moving forward!

Ultimately, though, two key questions stuck in my mind, the answers to which might inform my next steps in how I approach golf:

Is the game more fun or fulfilling for someone better than I am?

How much would it cost financially and time-wise to increase that feeling of overall enjoyment?

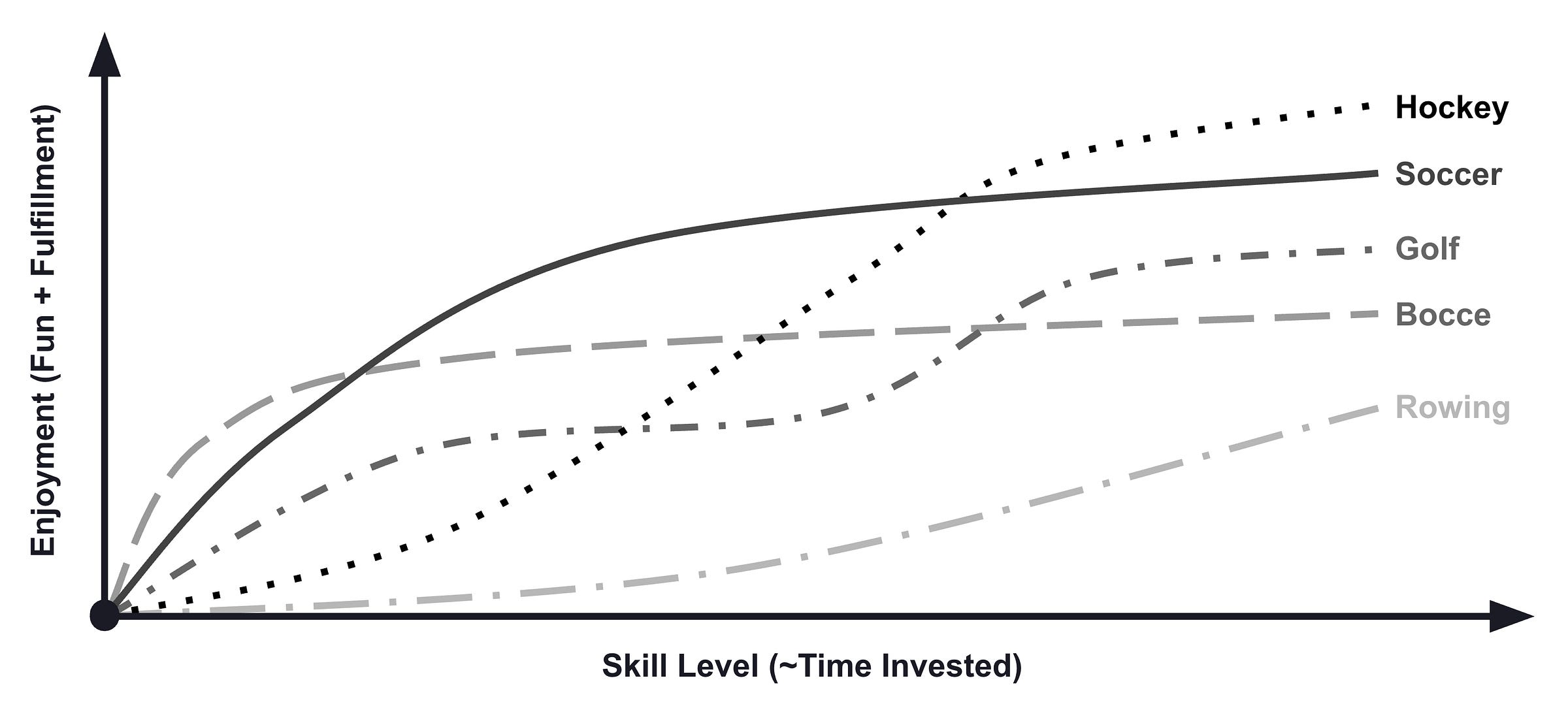

Beyond my personal journey with golf, these questions seem relatively universal. I think they apply not only to any new sport that people try, but also to any new hobby more broadly. Last year, my sole co-author Leo and I briefly touched on the confluence of time investment, cost, and fun through the lens of pickleball’s meteoric rise and broad popularity. Mirroring the implicit definition of “enjoyment” in the the questions above, we suggested that the combination of fun and fulfillment drive the overall enjoyment of a sport. More importantly, enjoyment of each individual sport has a unique relationship to the players’ skill level (at least on average). If you plot “Enjoyment” against “Skill Level,” which is really a proxy for time investment, you end up with a unique curve for every game:

Despite being a potentially overly analytical approach to assessing something as simple as fun-ness, I think this relationship proves quite interesting to study (at least in this nerd’s opinion). The core competencies required to engage each game at any level serve as a major forcing function for the shape of each sports’ curve. However, what I’ll call the “superstructure” for a sport that governs how it scales in terms of difficulty for players as they improve really plays a large role in determining the shape of the curve as well, especially in its initial phases. I rarely, if ever, see detailed discussions about the ways that whole sports “onboard” new players, but if a new hobby mimics new encounters with strangers, then a first impression is often a lasting one— if something immediately challenges you too much in a first interaction with a sport, it’s not likely to be durable relationship.

Of course, every sport asks its players — no matter their level — to learn and eventually master certain skills that vary in quantity, diversity, and difficulty depending on the sport itself. For players of any skill, golf demands high degrees of consistent, precise hand-eye coordination and full body control. For new players like me, there’s an added layer of physical fatigue because I (unfortunately) lack the core and arm endurance to swing a club more than 20 times without getting tired and wanting to take a break in the cart. This fatigue compounds with the complexity of the full golf swing to create significant variability in my shots, especially with woods and irons.

Interestingly, I think sports like curling, baseball, and even gymnastics all pull on similar threads when it comes to high demand for repeated full body control exerted in short bursts. Other games like chess almost steer entirely clear of physical demands, and lean heavily into mental and psychological skillsets. Meanwhile, sports like soccer, boxing, and basketball layer in more physical coordination and stamina on top of a significant hand-eye requirement. Tennis, hockey, and lacrosse seem to further up the ante in this regard— adding specialized equipment that acts as an extension of the arms, making the entry barrier even steeper for some. Hockey also has the double-whammy that it has instruments attached to the feet as well, and the act of skating is a completely unique skill for most— similar to skiing or most other action sports like snowboarding or skateboarding, for example.

In general, an increased quantity, diversity, and/or difficulty of skills steepens the learning curve, effectively decreasing the rate at which you improve in overall effectiveness in a sport. Notably, we are not trying to chart the relationship between time investment and skill here, rather we’re looking at how the skill level interacts with the level of enjoyment. In this regard, the impact of overall skill requirements inherent in a sport have a less clear relationship with the dependent variable, overall enjoyment. Sports with relatively low skill requirements can be immediately fun, which makes them highly approachable. Anyone can lace up sneakers and hop into a pickup basketball game or go for a group run with a local club, have fun, and also start to see quick improvement.

Strapping on skates to play hockey for the first time can be a different story. The skills required are numerous, diverse, and unfamiliar for most, which can make first impressions quite abrasive. However, when progress finally arrives — your first backwards skate, your first full-speed lap without clinging to the boards — the payoff tends to feel grander because you had to put in effort and you improved significantly. In the initial stages, I do think fun dominates the early stages of the overall enjoyment magnitude, but having this additional layer of fulfillment even in the early stages can really carry a sport in the long-run in terms of enjoyment. Even tic-tac-toe is fun when you’re just learning as a kid, but once you have mastered the only basic skill in the game, it becomes wholly unenjoyable (unless you love ties).

On top of the underlying skill requirement for each sport lies another crucial layer: the structure and governance of the game at each skill level. This includes everything from how fields, equipment, rules, team size, and even season formats adapt (or don't) from beginners to professionals. During my golf trip, I (fortunately) teed off from the fifth-most-difficult tee boxes if you count the unmarked championship tees that go up for major events. This artificial accommodation for my lower skill level made my overall experience better than if I were swinging from an average of 100+ yards further from the hole. Add on top of the closer tee box a quantitative compensation for my skill in the form of a handicap, and even I felt like I could compete with the best guys on the trip in different formats. Then add an even more approachable layer in the form of a scramble as our first event, and I think someone who had never golfed in their life could have just as much enjoyment as one of the more tenured golfers even if they just contributed a few shots to the team (speaking largely from experience).

Honestly, I think the intentional skill-based scaling of golf goes unrivaled in the wider world of sports as a complete package. Sports like soccer and baseball also scale elegantly with smaller fields, lighter balls, and lower goals for younger players, but lack some of the same compensation for adults getting into the game. For most sports, including hockey, tennis, basketball, fencing, football, and even spikeball, the basic equipment and dimensions largely stay the same, regardless of who's playing at what age (beyond very young youth leagues). Many of these sports do have shorter games relative to professional or even college leagues, but the overall mechanisms of play and scoring are the same for the pros as they are for beginners.

For sports that have steep learning curves where long-term fulfillment dominates overall enjoyment, it’s critical to offer intentional on-ramps for beginners. Superstructures that gently ramp up the demands for different skill types like coordination, endurance, strategy help keep new players from getting discouraged and inject some initial fun into early participation. Creating incremental wins early keeps the enjoyment curve from flatlining and builds momentum over time. Without these ramps, even the most promising new players can lose interest before they ever hit their first breakthrough: see my experience with tennis.

Beyond abating the overall skill requirement for beginners, I do think the team size plays an outsized role in affecting the skill-enjoyment curve, especially for the adult market. Anyone who's tried to wrangle five to seven adults for a weekly D&D campaign knows this pain firsthand, probably as well as any rec-league team captain. The act of trying to organize and wrangle large groups often presents a major barrier, instantly reducing the fun and increasing the friction to play— I think it’s no coincidence that individual sports have surged in popularity recently. People certainly began turning to sports like trail running and tennis and pickleball to have something to do in small groups during the pandemic, but the staying power of these sports’ popularity also lends credibility to the fact that having fewer people to organize is more enjoyable than managing a huge group.

In the end, the combination of 1) a sport’s overall inherent skill requirements, and 2) its onboarding structures and beginner accommodations really dictate the shape of the overall skill-enjoyment curve. For all sports, I think fun drives overall enjoyment in the early stages, while fulfillment plays a longer-term role in allowing a sport to reach higher relative levels of enjoyment. The interplay between the two creates a sport that attracts new players and keeps them around.

It’s surprisingly interesting to qualitatively analyze and plot different sports on the skill-enjoyment axes like we did for a few games above. At least for me, this process represents a new lens through which to assess the overall viability of individual sports in the long run. I highly suggest even hand-drawing your own examples for fun!

Of course, we also want to investigate the impact of financial cost to achieve different levels of enjoyment— or at least I want to since I’m staring down a largely unknown startup cost to get my own set of clubs and play golf regularly. Unfortunately golf serves to highlight the large disparities in cost scaling for individual sports (on the high side). For golf, expensive clubs, course bookings, and even lessons work well in unison to drive the high cost for someone looking to improve their overall ability. More broadly, the cost of basic gear required for a sport, local and long-distance travel, venue booking fees, any on-going payments, and even the infrastructure set up around gear rentals all factor into the overall cost for a sport at different stages of commitment by an athlete.

Somewhat ironically, I think many of the sports that have very high costs associated with increasing enjoyment also exhibit relatively steep learning curves to begin with. This combination of which can produce somewhat of a negative feedback loop and make a sport even less enjoyable. Anyone who has spent $300 on a day pass to ski and booked rentals only to struggle through ill-fitting boots and poor conditions while learning to ski knows that the added stress can make learning even more difficult. I don’t have any first-hand experience, but I imagine that the same holds true for a budding equestrian (yes, this is a noun). Owning a horse is absurdly expensive, and I’m sure the initially steep learning curve makes the upfront capital investment feel even more limiting and potentially detracts from the experience.

On the flip side, some of the lowest cost sports out there also have very shallow learning curves that allow for some fast fun, the combination of which can get people hooked. The first time I played pickleball, I was wearing running shoes I already own, used a paddle set that a friend won in a giveaway, and played at a local public park for free. I had a great time, and the fact that it was effectively free for me to try helped make the day more enjoyable. Other sports like soccer and basketball have relatively low equipment costs and similarly strong public infrastructure in many parts of the world, but once you reach a decently high skill level, you start paying really high costs for coaching and travel, especially as a youth athlete.

Every sport seems to have a unique set of cost factors that actually express in different locations along the skill-enjoyment curve. Layering cost into the plots for the sports listed above in the form of color yields some really interesting visual results that tell a surprisingly nuanced story about an athlete’s journey in different types of sports (if they don’t end up going pro and they actually have to pay for everything along the way). In the absence of a better idea yet to originate in my brain, I’ll call these skill-enjoyment-cost curves “Hobby Plots.”

Someday I’ll get a Matlab license again for the first time since undergrad and make some actively manipulable 3D charts of these curves. Until then, I think this 2D view really does a good job of demonstrating the unique form of every sport’s Hobby Plot. Given some more time, or perhaps in a future article, I would love to delve into more individual sports and actually try to map the form of the curve along all three dimensions to both the demographics of the sport and their overall popularity. I think there’s likely a ton of value for existing sport governing bodies and potentially even new products lurking in the details of these curves, even if they are qualitatively derived.

Most importantly, though, I’ve done my best to place myself on the curve for golf in the current moment. There’s no doubt in my mind that I can begin to slowly ramp up my overall enjoyment of golf as a sport by playing more and increasing my skill level, likely through a combination of greater fulfillment in better scoring and maybe even a bit more fun (although I have a blast already). However, I also sit on the precipice of increasing my costs substantially. I don’t have the budget for a new set of clubs, lessons, and rounds at the moment, nor the time to actually use all that in practice.

As a result, I think I’m actually sitting in some nice little local, stable equilibrium, where I can comfortably say that I’m having a lot of fun and enjoying myself substantially while not overexposing my costs or time commitments to the sport. I will definitely still play when the opportunities arise and I can borrow or rent some clubs, but I think it’s unlikely I’ll pursue a significant investment in lessons or rounds on my own. Might this conclusion be a somewhat destructive and self-fulfilling one to draw from pure logic? Absolutely, but I did say that we would be overanalyzing fun with this overall plotting process— copy my steps at your own peril unless you are an analyst trying to launch a new sports product!