Recess #14: Why Are Sports the Way That They Are?

Trying to understand the logic behind the number of players participating on the field in team sports

Why does each professional soccer team have 11 players on the field at once? How did the MLB decide to have 9 players on the field for defense? Most importantly, why doesn’t ping pong have a team triples match format— why did they stop at doubles?

These types of questions have bounced around my head for years ever since a friend pointed out that most large team sports have an odd number of players on each team playing at once (which is kind of true) . It seems like the same question must have split some sports governing bodies as well since numerous sports have independent versions in which pros can compete with different team sizes. Rugby might be the most egregious example, with three separate popular versions requiring teams of 7, 13, or 15 athletes per team. Of course, some paddle/racket sports like tennis, ping pong, and badminton have singles and doubles while many racing sports including bobsleigh, rowing, canoe sprint, and kayaking all have variable team sizes with rowing ranging from 1 individual up to 8 people.

Once you leave the realm of individual sports, the question about how to appropriately size teams seems to yield somewhat random forcing functions when you review a rolodex of pro sports in your mind. The types of factors that could influence a decision about how many players should be on the field for a sport could easily overwhelm decision makers (we’ll talk about them later). In reality, though, I would guess that the size of most team sports was initially established more or less based on vibes through trial and error. It’s easy to envision that a basketball court with teams of either 2 or 20 players would yield too slow or too chaotic games, but picking 5 specifically was probably based on intuition more than anything else, if I had to bet.

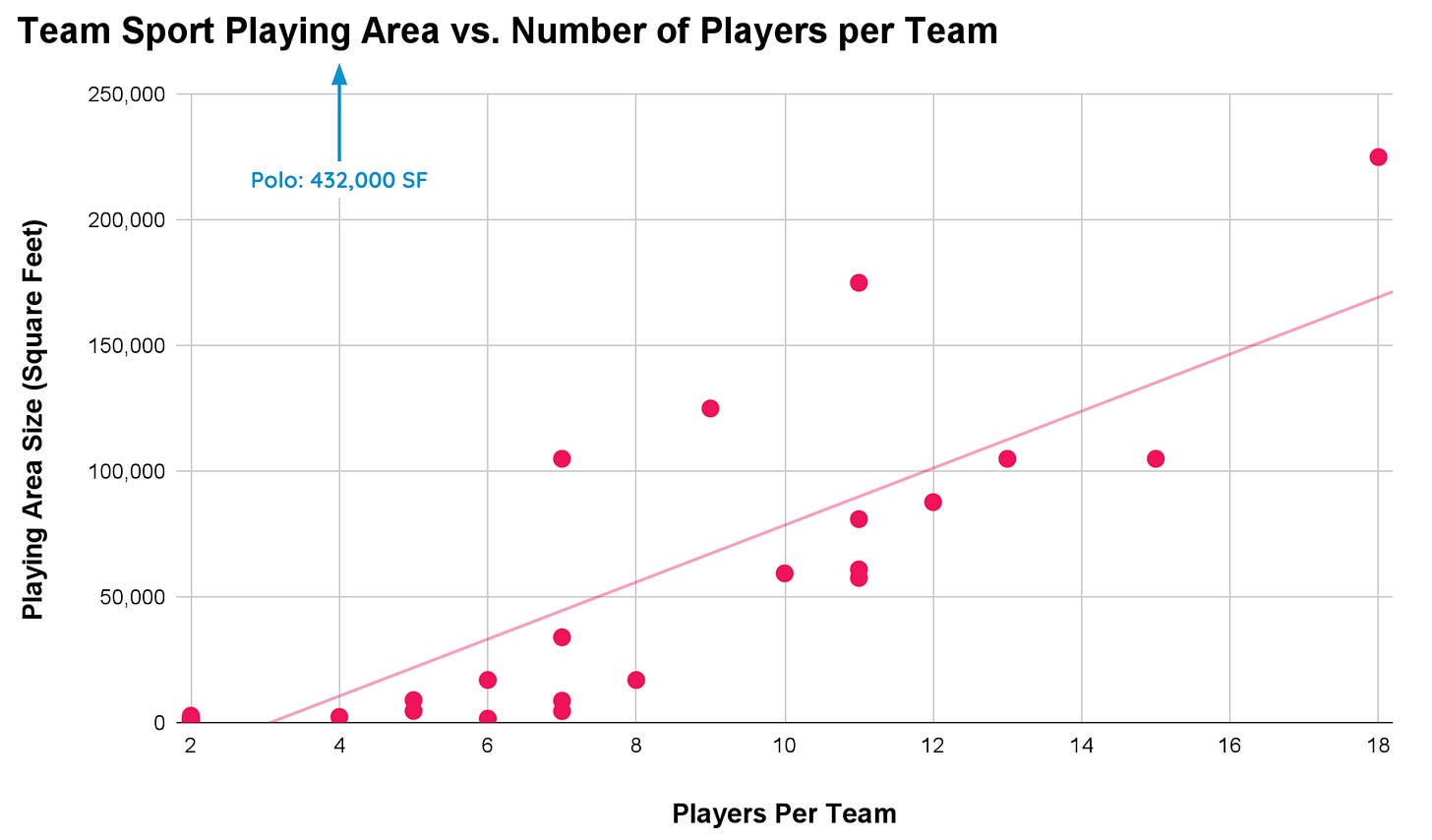

Despite this hunch about the somewhat arbitrary selection process, I started searching for different relationships between team size and other facets of the respective games. It turns out that the number of players on the field for each team maintains a relatively linear relationship with the square footage of the playing surface! That is, unless you are a horse instead of a person…

The plot above captures the team size and playing field size for 30 global team sports (plus polo) ranging from 2 players up to 18 players with Aussie Rules Football (what’s going on with this sport). The strong linearity of the relationship surprised me upon first viewing, with the apparent “norm” for picking a playing surface size being roughly 11,500 Sq. Ft. times the number of players minus 34,500 Sq. Ft. When inverted to determine the ideal number of players per team in a sport based on playing field size, it yields:

Immediately, you may notice that this equation does not handle the sports with two players per team very well, since the default number of players per team on a court of zero area is 3. Of course, it’s not a perfect predictor for team size across the board with an R^2 value ~0.7. However, it does estimate the number of players per team in an unknown team sport with relative accuracy— or at least with more accuracy than I would have guessing blindly! With rare exception for sports like baseball and cricket with 9 and 11 players on massive fields, the estimation equation is surprisingly spot on. That said, the variability in the ratio of field size to number of players per team does highlight some of the major differences between individual sports and the conscious or unconscious decisions and factors used to determine team size when more than one athlete is involved per side.

I’ll keep the analysis light here, but at the highest level team sports with a lot of players seem to drive more strategic and oftentimes slower paces of play while sports with smaller teams seem to require greater demand for high-paced, more tactical play. The biggest reason for this divide likely comes from the fact that on larger teams, the time spent “off the ball” increases and the ability for teams to defend with multiple players increases, so structural formation and team movement provide more value in attempts to score. In a smaller sport like hockey or basketball, structure and strategy are still important, but the amount of time a star player can handle the ball and only face 1-2 defenders increases greatly compared to something like rugby union.

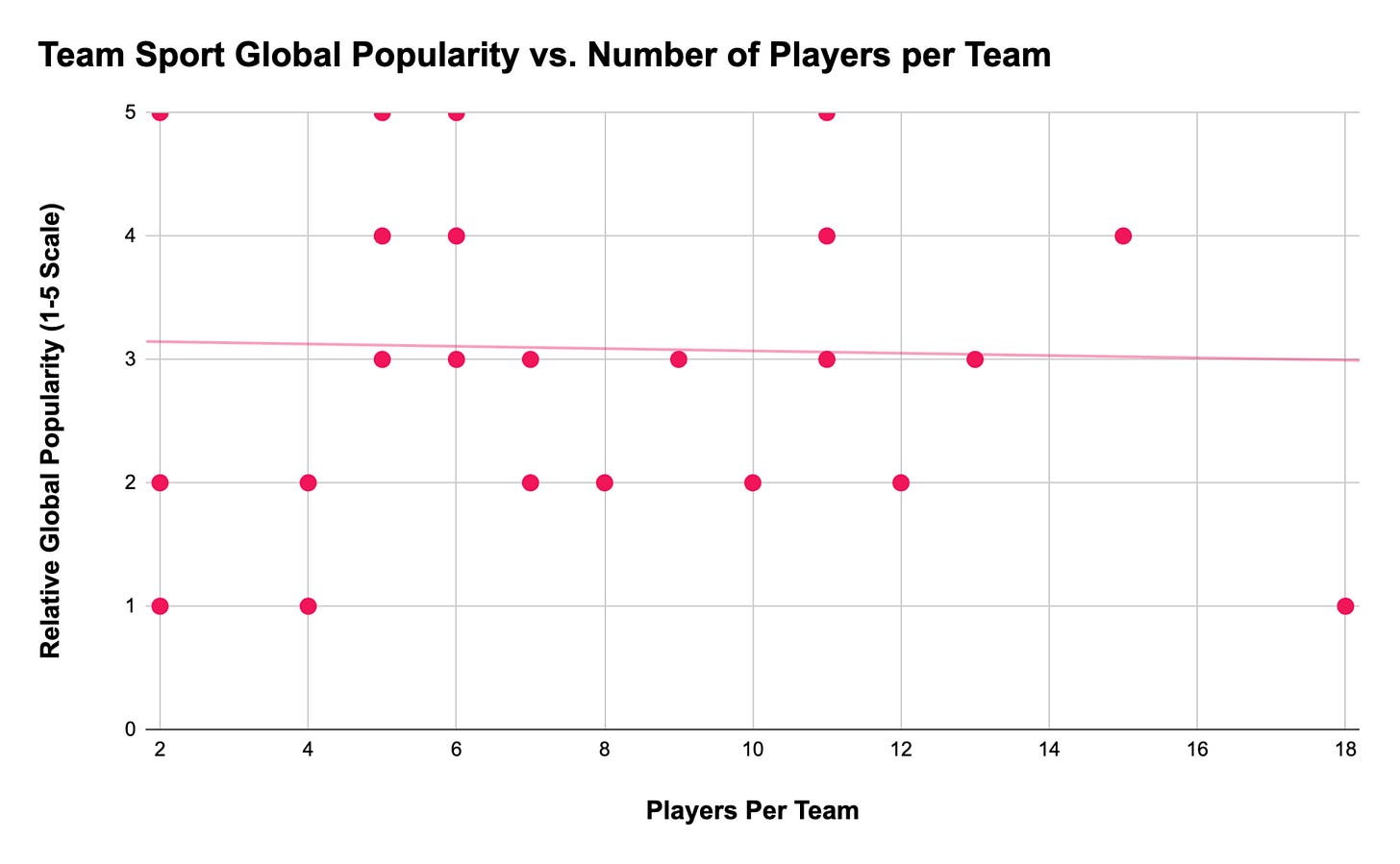

I would posit that the smaller team size may drive increased specialization among a team and more short-term/fast-paced entertainment for both fans and players. Smaller team sizes may also help breed star athletes more easily because they can affect winning more readily and also get more time to shine. Interestingly, though, there’s effectively no correlation between the number of players on a team and the popularity of the sport globally:

I’d be remiss if I didn’t highlight the low sample size for these analyses, with 31 total data points, but the initial results here challenge a lot of my own expectations about team sport size and its relation to popularity. I feel confident in the results, but I would not have guessed there is such a linear relationship between field size and players per team, and certainly not that the global popularity of a sport has no relation to the number of players on a team— at least in the range of modern team sports. The latter is particularly surprising to me because I thought sports that structurally produce super stars and faster-paced play might be more popular, but this might be a topic for a future article! I feel like I’ve only skimmed the surface on the correlations between sport popularity, team size, and other inherent features of games that we take for granted.

Even with all this information, though, we still wouldn’t answer a different fundamental question: why aren’t there more live-play team sports with asymmetrical numbers of players? Many sports like soccer, hockey, and lacrosse use player count asymmetry as a tool to punish teams, but why there aren’t any constant-play sports with that as a default and different structural advantages for the team with less players will have to be a question we also answer in a future article. In the meantime, enjoy three Japanese national team soccer players take on 100 kids in the most asymmetrical game of all time (no spoilers on the winner):

There’s the bell!