Dr. Duopoly's Perceived Consolidation of the Ski Resort Market

How the dominance of two companies has shaped modern mountain experiences

This past winter, I was fortunate to visit Steamboat Springs with some friends for a week-long trip chock full of activities including cross country, backyard igloo building, snowshoeing, beer tasting, and of course some resort skiing. Apart from our flights to/from Steamboat (shoutout to JetBlue for direct flights to local Hayden airport from both Boston and even Miami), the most expensive individual purchase of the entire trip ended up being a friends’ day pass for the mountain. The 1-day ticket for one of her first full days of learning to ski clocked in over $300, a whopping price that even shocked me despite my familiarity with the current ski resort landscape. There was no option for a half day ticket, and peak season pricing was clearly in effect. With gear rental and parking, the total cost for a day of skiing came in ~$450.

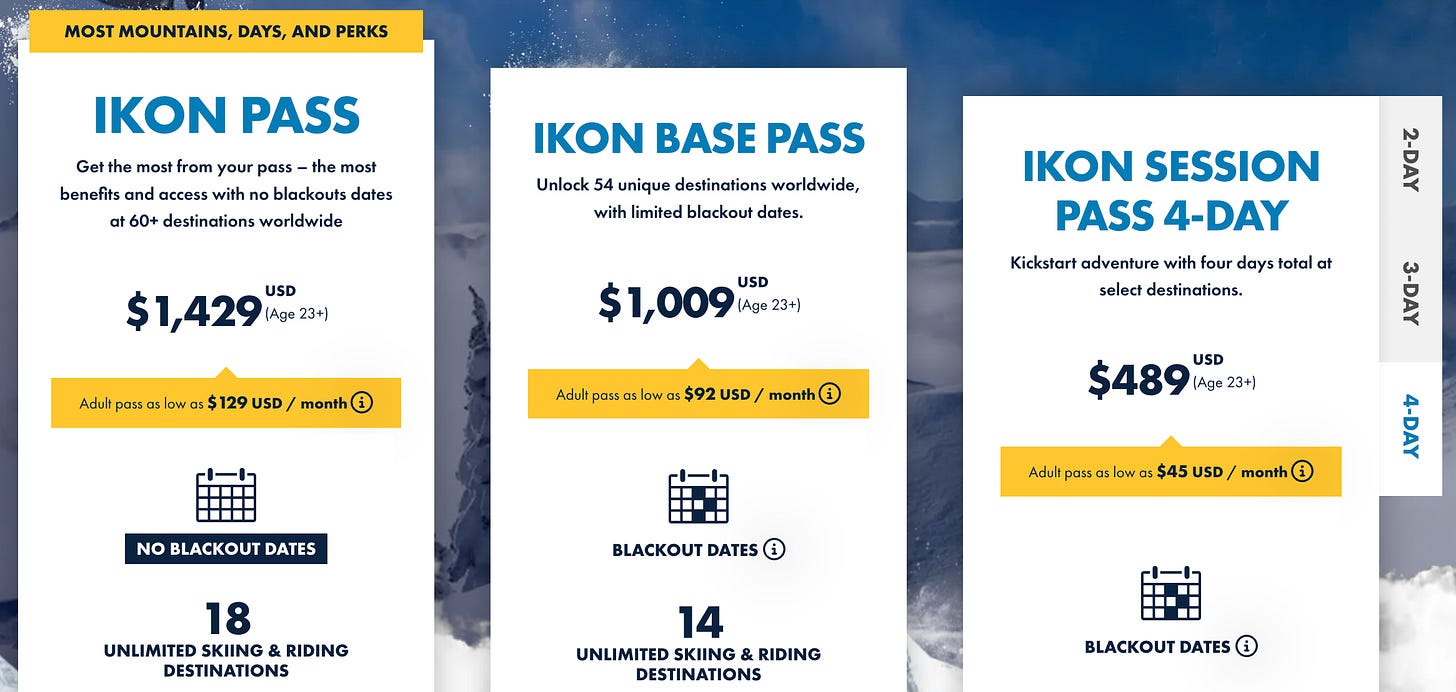

The cost of this single day pass represented nearly 3/4 of the price I paid for my 4-day Ikon Pass in the summer of 2024, and ~1/4 of the full Ikon pass some of our other friends had purchased en route to skiing ~20 days in the season (an effective daily cost of ~$60). I was reminded of this experience and price disparity while purchasing this year’s 4-day Ikon Pass earlier in August (I’m honestly later than many skiers prepping for a new season pass purchase). Despite being the height of summer heat, I wanted to escape to winter for a bit to write about how the consolidation of many major ski resorts into two well-known brands— Vail Resorts’ Epic Pass and Alterra’s Ikon Pass— has changed the modern skiing experience. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the unification of the ski resort market, and a brief “before times” history of the two most controversial players in the ski industry seems warranted!

Vail Resorts opened in 1962 with a single resort (the eponymous Vail Resort) along I-70 in Colorado, which is a modern weekend skiers’ purgatory for anyone who has experienced it. The company has been acquiring resorts, and has been public, for nearly 30 years (a shockingly long time). In 1996, Vail started steadily expanded its ownership of resorts to a current total of 42 across the U.S., Canada, and Australia and sits at a market cap ~$5.7B, down from over $10B in 2021. With a growing number of resort operations and partnerships, Vail launched the Epic Pass in 2008— the first major multi-resort all-you-can-ski pass that initially cost less than $600. The pass slowly converted skiers into locked-in season-long customers and shifted Vail’s revenue base from less consistent walk-up tickets towards predictable recurring pass sales (~65% of its revenue today). Despite its massive revenue growth, investment in resorts and infrastructure, and an increasingly expensive Epic Pass ($1,050 this year), the company’s profit margins hover around 9–10%.

Depending on how you look at it, Alterra Mountain Company might be the younger, scrappier rival to Vail Resorts. Throughout 2017, the private equity firm KSL Capital Partners and the Crown family (owners of Aspen Skiing Company) went on a ski resort acquisition spree, absorbing Intrawest, Mammoth, Deer Valley under the same umbrella as the other resorts already under Aspen control. In 2018, Alterra was founded, and the company quickly launched the Ikon Pass— its mirror product of the Epic Pass that provided access to Alterra resorts. Despite being a privately-held company to this day, Alterra has come to rival Vail’s expansion aspirations, and now offers over 50 mountains on its Ikon Pass, though actually owns and operates ~1/2 the resorts that Vail does. In just six years it’s become a global passport for skiers who want variety but don’t necessarily want to bankroll Vail’s empire.

While Vail has historically focused on vertical integration and consistency across its growing empire of 42 owned/operated properties, Alterra has relied on resort alliances and brand diversity, giving skiers a broader but less standardized network. Despite their differences, both business models condense down to a reliance on consistent revenue generated through pass purchases to both normalize income throughout the calendar year and help increase enterprise value. To have compelling pass value proposition for the largest possible skier base, the business models rely upon a strong base of premium-to-luxury resort ownership in order to cover broad geography and demographics. In establishing this base of resort ownership, both companies have been wildly successful in recent years and have consolidated much of the large-scale US resort market along the way.

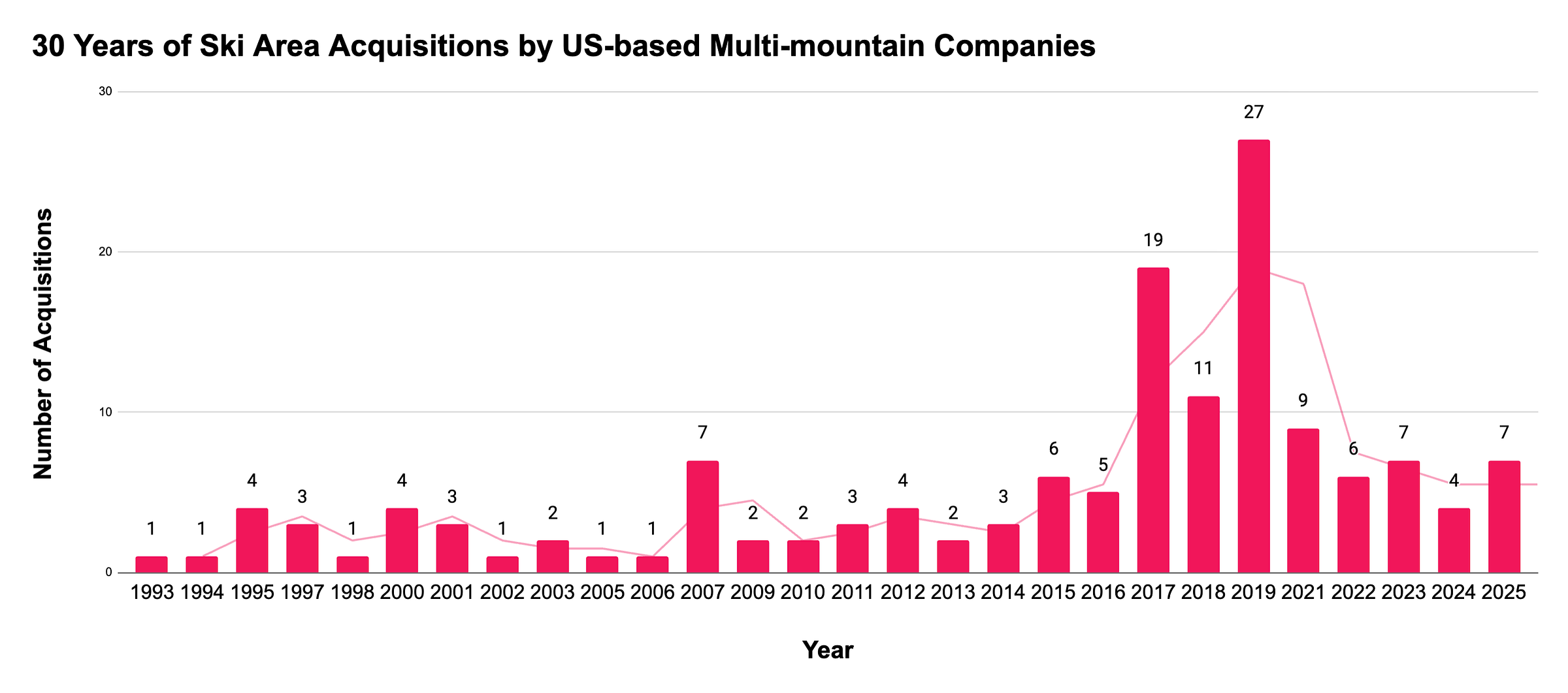

The data above is provided by The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast, who have an incredible online database of ski resort information— I recommend subscribing to their Substack if you love the business of skiing!

There’s a lot to unpack in the resort acquisition timeline above— since 1993, multi-mountain ownership groups have made a whopping total 146 acquisitions! However, Vail Resorts and Alterra account for only 57 of them, which is a shockingly low quantity. The vast majority of ski mountain acquisitions actually belong to a long tail of smaller players that tend to own regional clusters or single resorts—names like Boyne Resorts in New England, Powdr in the Mountain West, and the aptly named Wisconsin Resorts in the Midwest. For those curious, the one ski resort in Alabama that just has a tow-rope and claims 1” of annual snowfall per year is still independently owned and operated.

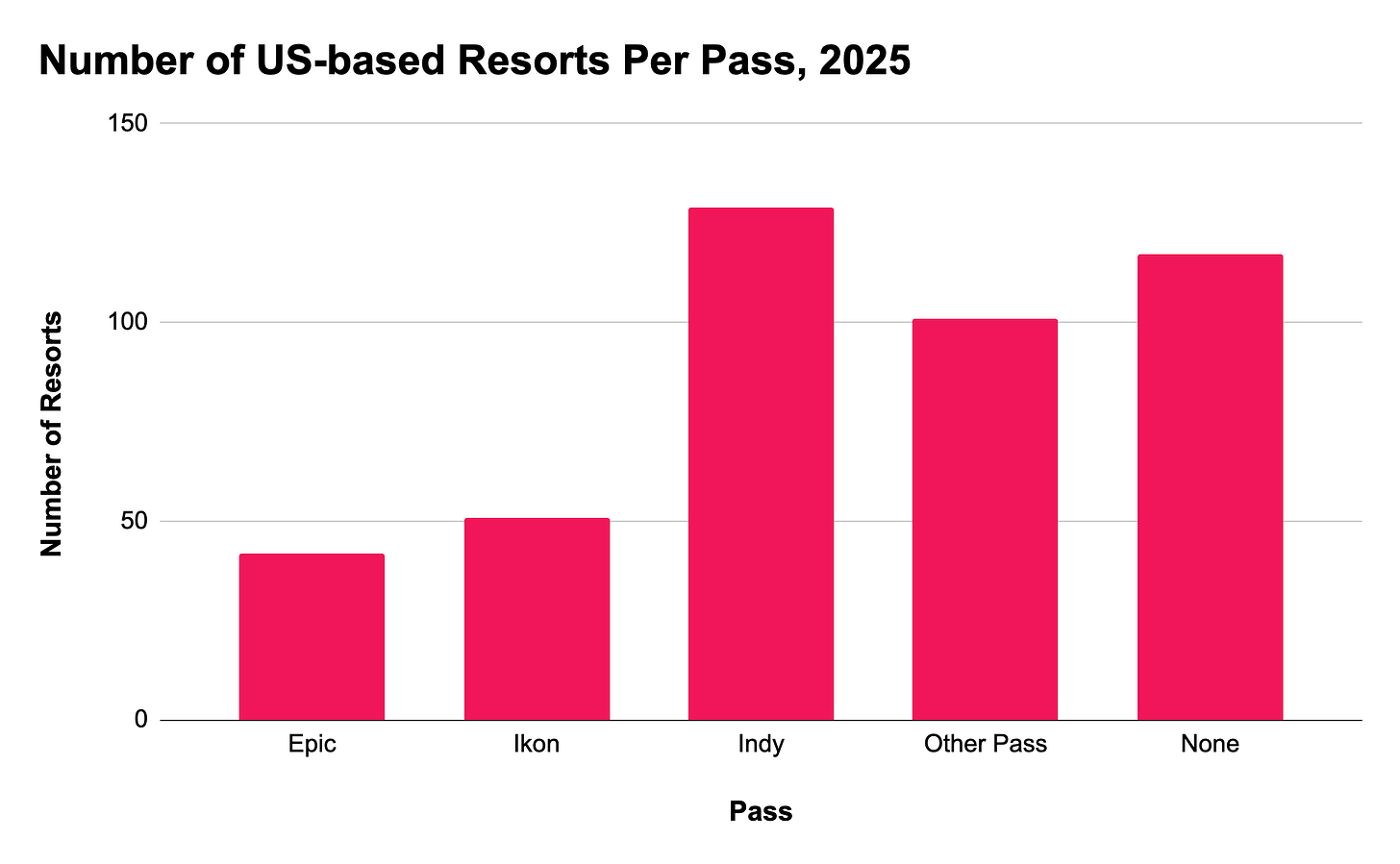

A couple of interesting patterns emerge from this underlying information behind the initially scary consolidation chart. First, Vail and Alterra feel omnipresent because they dominate headlines and own many of the marquee resorts in the Mountain West (Vail claims to alone service 50% of skiers in North America), but they don’t actually own that much of the total market by resort count. Alterra also gets out-sized visibility thanks to its Ikon Pass product specifically because it grants access to 30+ resorts that Alterra doesn’t actually own, making it look like it controls the entire map when they don’t. Second, about 64% of U.S. ski areas (with lifts) are now tied to one of the “mega passes” (Epic, Ikon, Indy, Mountain Collective, Triple Play, and others), but only about one in five are covered by the Epic or Ikon pass specifically. The quiet giant here is the Indy Pass, which corrals roughly 130 ski areas—about a third of all lift-served mountains—despite not owning a single lift tower itself.

There’s no doubt that Vail and Alterra have consolidated certain regions around the U.S. (especially the high-profile tourist resorts) but there’s still far more variety and independence left in the broader resort industry than I expected. With that said, though, Vail and Alterra’s impact on the overall ski resort industry in North America is unparalleled, both in negative and positive ways.

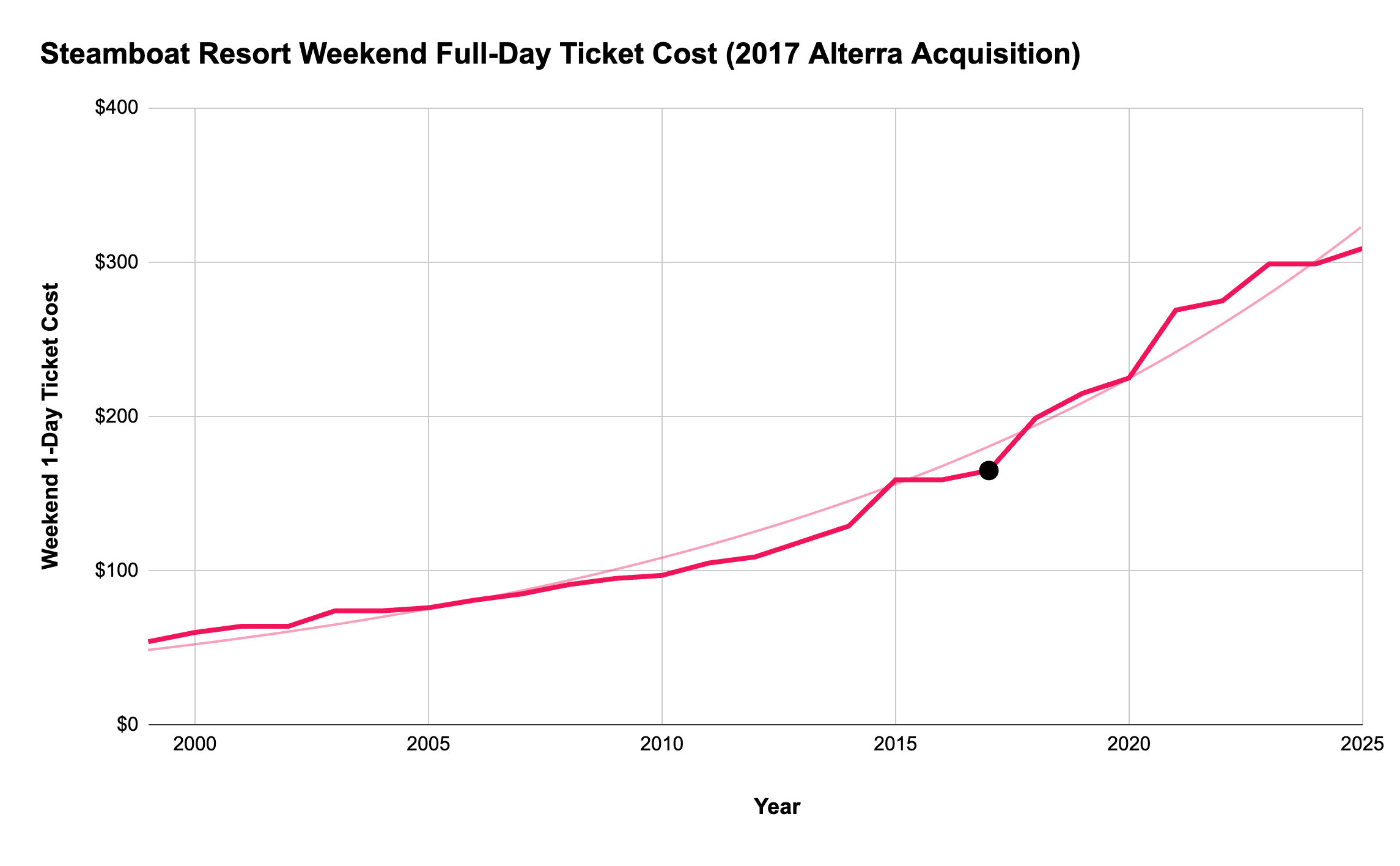

The most salient drawback of the Vail/Alterra era is increased costs to ski or snowboard at popular resorts, particularly for individual day passes (which they are trying to dissuade people from buying). Of course, some inflation happens across the whole ski area world as operating costs have increased for all resorts. In New Hampshire, for instance, Cannon Mountain (which is operated by the state) charged $79 for a weekend day ticket in 2012–13, and $125 last season— a 58% increase vs. 38% CPI inflation over the same period. However, a Steamboat 1-day ticket rose from $109 to $309, a 183% increase (!!!) that epitomizes the more severe cost ramp for Vail/Alterra-owned mountains. Nationally, the average window rate at big resorts has more than doubled since the mid-2000s, with many other areas like Park City also topping $300 a day now. The multi-mountain passes help regulars dodge those astronomical prices, but for occasional skiers or families trying to squeeze in a single weekend trip, the price barrier has never been higher to hit the slopes on a resort owned by Vail or Alterra.

Another downside is the way these companies push resorts to find “new revenue streams,” often in ways that feel forced. Parking fees, high-priced dining, lodging minimums, and even line-skipping upsells (think “express lanes” for lifts) have become standard at corporate resorts. The basic justification is that massive capital projects—new lifts, snowmaking systems, base villages—need funding, but locals often see it as extracting every possible dollar from a captive audience. That tension can erode goodwill, particularly in places where these resorts were once community institutions. The cost of bringing a family of four to a condo at any major resort in the mountain west for a week must be over $10,000 at this point with lodging, travel, food, and tickets included (if the meal costs at lodges are any indicator).

To be overly simplistic, increased costs due to demand for business growth and alternative revenue models have instigated the majority of modern industry facets (mainly cost) that drive the pushback against Vail and Alterra. It’s also worth mentioning that there are surprisingly few economics of scale benefits to owning multiple resorts. Of course, overhead and other corporate function can be consolidated and some discounts can be had for equipment, but mountains are so independent and unique that it’s difficult to reduce costs by scaling through disparate mountain acquisitions alone.

With that said, though, some genuine upsides to consolidation do exist. Multi-mountain passes have made it easier than ever to explore new terrain without blowing a budget. Especially when we were receiving student discounts, my wife and I used our Epic and Ikon passes to test out a bunch of different resorts throughout Colorado that we otherwise would not have tested. Especially an Indy Pass nowadays— it’s possible to visit half a dozen resorts in one season without thinking hard about incremental costs. For travelers, this flexibility can be a big win: one year you might find yourself at Vail, the next at Steamboat or Jackson Hole, all for roughly the same sunk cost. It’s a level of choice and convenience that didn’t exist in the single-mountain pass era, BUT one that admittedly can only be enjoyed if you can afford a $1,000+ pass every year.

Interestingly, the same drive to unlock “new revenue streams” that promotes unfriendly consumer behavior on the mountain during the ski season has led many mountains to reinvent themselves as year-round playgrounds. Lift-served mountain biking, zip lines, alpine coasters, and hiking trail networks are becoming more standard for major resorts, which ideally attracts more year-round visitors to resorts and towns that typically have less consistent seasonal traffic. While this effort may be a bit of a loss-lead in the short term, hopefully it does begin to help balance mountain revenues year-round and reduce skiing costs (though I’m not holding my breath too hard).

At this point, it's worth zooming out to the bigger picture in the U.S. ski industry, which has only gotten more popular. The 2022–23 ski season chalked up over 65 million skier visits, marking the busiest domestic season ever on record, and nearly 20 million more visits than the 1982-3 ski season 40 years earlier. Existing resorts keep adding gondolas and high-speed lifts, but the 1982 ski season also represented the last season that included a new major resort in the US, with Deer Valley, Utah breaking ground in 1981. Peak Rankings has a great article about the stagnation of new US ski resort launches since the 1970’s, and the constrained national supply has almost inevitably led to increased prices for customer as demand has risen (if I learned anything from my Intro to Econ course, which is a stretch). Absent any other forces like business model transformation and industry consolidation, it’s not extremely surprising that resort skiing in the US has become much more expensive (though it still sucks).

Regardless of the underlying forces, the overall resort skiing industry is experiencing massive, structural changes and price upheaval right now, and it will be fascinating to see what happens next.

Frustrations with Vail Resorts boiled over last December (2024) during the holidays as ski patrollers at Park City went on strike, complaining of unsafe conditions and low pay. Vail initially tried to fill shifts with managers, but chaos on crowded holiday slopes made that untenable and the strike ended in January 2025 with concessions from the operator. This whole experience left a sour taste for both the visitors to the resort and locals, many of whom were actually part of the strike or supported it directly. Despite the unrest in Park City not leading to more dramatic changes, the town of Nederland, Colorado took matters a step further, announcing in July 2025 that it would buy back Eldora Mountain Resort from corporate owner POWDR using resort-backed bonds. The resort will (for now) stay on the Ikon Pass, but all 700 employees will transition to become town employees under the new model, making Eldora one of the first resorts to return to community hands in decades. It would not surprise me if this model becomes more common around the US once its proven successful, especially for smaller mountains.

Beyond independent or community-based takeovers of resorts owned by conglomerates, for many skiers, the next frontier may lie outside the United States. No European resort charges more than about $95 per day, meaning American prices are often three to four times higher. For many, it’s now cheaper to book a trip to the Alps than to buy a long weekend of Colorado day tickets, which is actually quite similar to how Europe became the preferred/cheaper destination for many Taylor Swift Eras Tour attendees. I would not be shocked at all if some combination of skiers reverting to more bare-bones resort experiences and new resorts popping up through permit and regulation relaxation drove 1-day prices down to the range of European mountains over time, especially at smaller US mountains. The continued proliferation of uphill and backcountry skiing might support this theory as well!

Finally, it’s worth mentioning the complete other end of the affordability crisis, where some see opportunity in privatized mountain models. These member-only mountains tend to be small, and do exist fairly ubiquitously across the US. Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings believes that the private-public model could be proliferated to offer a more upscale experience to those who want it, and has invested over $100M in developing Powder Mountain in Utah to this end. While I’m not necessarily a believer in this stove-piped, exclusive vision long-term, perhaps it does help make “normal” resorts more affordable because they lose purchasing power of their customers that spend the most if they leave for private slopes!

At the end of the day, I find the future of the ski resort industry extremely unclear, and we didn’t even talk about the potential impacts of climate change! However, researching and writing this article has also raised questions about the clarity of the current industry state too. Going into this article, I thought that both Vail Resorts and Alterra would be clear evil villains that had taken over 90%+ of the ski resorts in North America while leaving no path for recovery or outlets for skiers to find cheaper options. The recurring revenue model and hunger for growth that these (and many other) multi-mountain owners take into the resort industry has had clear cost impacts for skiers and their aprés-only friends and family. However, their presence has also generated new mountain activities and also created new multi-mountain passes like the Indy Pass.

Although I don’t think I have come to a firm conclusion about the black-or-white nature of the current market players, this trip through the market and its history has been fascinating. It’s also left me with a core question I can’t get out of my mind: What happens to these big resorts when there is inevitably a retraction in demand for skiing/snowboarding more broadly? Do they just not operate some parts of a mountain or let the forest re-grow when they can’t afford to keep it all open?

It’s a line of questions worth pondering in a future article…

Cam, great writeup. I wanted to share a personal angle as someone who grew up in the PNW doing a bit of skiing but also spending a lot of time camping and backpacking.

I think there is an interesting comparison to be made between the way the growing demand for access to alpine skiing has been handled by the skiing industry and the way that public land access has been managed over the last twenty years or so.

Like skiing, there has been a big run up in demand for access to backcountry campsites and recreation in general. However the method of limiting access has created a system that demands more guts or effort from a user than skiing's pay-to-play model. When I was in my 20s the mantra was that you had to get up earlier, drive farther, and hike longer than Johnny Q. Public if you wanted to get beautiful solitude without having made a permit reservation far in advance. Compared to skiing, there was better access for someone with a lot of time and energy, but not a lot of extra income.

An example I had in mind was the Enchantments alpine backpacking area in the Central Cascades. It has a permit lottery with tens of thousands entering every year, and has around a 6% success rate. However, if someone were to backpack the next drainage south, the Ingalls Creek drainage, they would get something 99% as nice but with a self-issue permit box at the trailhead instead of a very over-subscribed permit lottery. On a more macro scale, in Washington State it is often difficult to get in to Mt. Rainier or Olympic National Parks during the summer, but if one drives a little farther, North Cascades National Park is a real gem that has no entry fee and a lot of opportunity to hike without big crowds.

I think there will continue to be opportunities for the savvy ski vacationer, whether it's leveraging less well-known pass alliances or going to further flung resorts. Similar to outdoor recreation in the summer, there is still a reward for not simply following the crowd to the big resorts. I hope this translates to business success at the more modest resorts around the USA.